Some readers may find this story distressing. For a searchable list of crisis lines and other support resources across Canada, please visit this federal government web page.

Yolanda Bird was seven years old when she discovered her older brother had killed himself at the age of 10.

“Going through the loss and the grief and recovery of all of that has taken me to where I am today,” Bird said. “It didn’t happen overnight. It took me years to actually come back from healing and just reconciling with all of the things that he left behind, all of the trauma.”

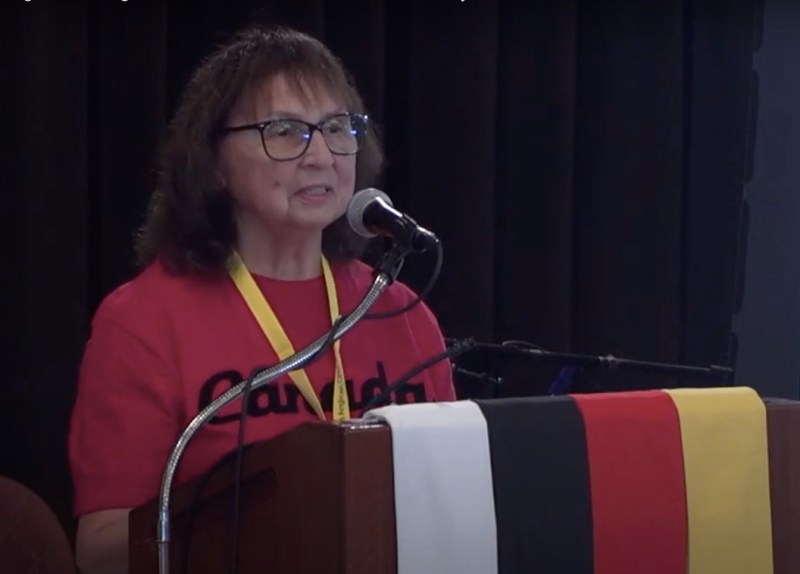

Today, Bird, a suicide prevention worker for the Anglican Church of Canada in Alberta and Saskatchewan, works to prevent others from having to deal with the same trauma. Suicide, she said, “hits everyone. It hits the community, it hits the families.” A 2019 Statistics Canada report found that First Nations people in Canada die by suicide at three times the rate of non-Indigenous Canadians. Meanwhile, suicide rates are twice as high among Métis and nine times as high among Inuit as for non-Indigenous Canadians.

Bird told her story to Sacred Circle on May 31 during a session on the suicide prevention work of Indigenous Ministries—one of a number of discussions dealing with the crisis facing Indigenous communities. Two days earlier, the national gathering of Indigenous Anglicans heard a presentation on Pitching Our Tent, an appeal to support the Northern Manitoba Area Mission in the Indigenous Spiritual Ministry of Mishamikoweesh. The appeal includes partnering with organizations such as the Great Sky Sovereign Trust, a company which describes itself as promoting economic self-determination in Indigenous communities.

Great Sky founder and president Allan “Greatsky” McLeod described to Sacred Circle a “national crisis” of poverty, food insecurity and homelessness among Indigenous populations in Canada. McLeod cited growing poverty rates, with the population of Indigenous people living in poverty jumping from 32 per cent in 2016 to 44 per cent in 2020. Half of those people face food insecurity every month, a problem McLeod said was worsening due to inflation and rising living costs. He pointed to severe overcrowding and housing shortages in Indigenous communities.

The Rev. Norman Meade, an Anglican priest and Métis elder who is co-director of Pitching Our Tent, described in emotional terms the devastation wrought by poverty in Indigenous communities.

“We see our people suffering,” Meade said. “We see shortages. We see our church is struggling… We lost many of our people and we’re still losing them today.”

A major focus of the 2023 Sacred Circle was reaching consensus for the Covenant and Our Way of Life, founding documents for the self-determining Indigenous church within the Anglican Church of Canada. But Meade asked how self-determination is possible in the face of material scarcity.

“My hope fades many times, because I wonder how can we go to be self-determining in the work we do in our communities and yet we’re doing it without any kind of resources [and with] shortage of food,” Meade said.

“We have to do something and we have to do it now,” he added. “We can’t wait and wait and wait, then die waiting … This is what we hope for … that God will hear the cries of our women, of our children, of our old men and our young men, because they’re dying in huge numbers.”

Suicide prevention

Rather than waiting, Indigenous Anglicans are taking action to address the crisis conditions on reserves, such as through suicide prevention led by Indigenous Ministries.

Dorothy Russell-Patterson, a suicide prevention worker and grief recovery specialist along with her husband John, led the session on suicide prevention at Sacred Circle. Russell-Patterson previously spoke about suicide prevention at the 2015 Sacred Circle in Port Elgin, Ont., shortly after she had started the program with the late Rev. Norm Casey.

At the 2023 Sacred Circle, Russell-Patterson introduced her team which included herself, John, Yolanda Bird, suicide prevention worker Dixie Bird and trauma specialist Canon Murray Still.

The greatest barrier to taking action on suicide prevention, Russell-Patterson said, is stigma.

“We want to reduce the stigma of suicide so that families and communities can begin to explore life-building strategies … Reducing stigma is time-consuming and it took us two years to get ourselves off the ground and known in the community and accepted,” she said.

Since 2015, suicide prevention work has included building relations with Tataskweyak Cree Nation, which declared a state of emergency over high suicide rates in 2021. Russell-Patterson received a call the following year from Bishop Isaiah Larry Beardy about Tataskweyak, his home community, which had experienced 22 suicides and more than 400 attempts during two years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

She made a trip there and brought along a curriculum for K-12 students developed by the federal government on suicide prevention, which focuses on the importance of building self-esteem and a sense of identity. A local school principal who heard her talking about the curriculum on community radio travelled to meet her, introduced himself and took away a copy of the curriculum. “The outreach was fantastic just by that radio communication,” Russell-Patterson said.

Suicide prevention ministry has also included participation in the pilot project “From Trauma to New Life,” which involves teaching suicide intervention skills for Northern communities in partnership with the Crisis and Trauma Response Institute; organizing a language and culture camp for families at Six Nations of the Grand River, Canada’s largest First Nations reserve; and offering Indigenous language classes for adults.

“Young adults have lost their identity … Once you begin to look at your own language and hear it and learn it … it strengthens you,” Russell-Patterson said. “It makes you become who you’re meant to be.”

Much suicide prevention, however, involves workers responding to individual cases. Yolanda Bird outlined one episode from last year, in which she went to check on a young woman who had reached out for help. When she arrived, her nephew, who was dating one of the woman’s relatives, came running out of her house and asked for help because the woman was trying to kill herself.

“I couldn’t think,” Bird recalled. “I responded very quickly.” She ran inside and went to the basement, where her initial relief at seeing the young woman gave way to shock when she realized the woman was hanging “maybe about an inch off the floor.”

“At that moment I realized that I had come too late, so I actually broke,” Bird continued. “But I went into my mental state of where my mother was when she had to deal with my brother and what had happened that morning that he took his life. So what I did was naturally I helped her down and I gave her first aid and CPR.”

Bird managed to keep the woman alive long enough for her family to say goodbye, she said. “I got her heart beating again.” When paramedics and police arrived, an officer asked who had given the woman CPR.

“I was scared to answer because I [thought] I did something wrong,” Bird said. “Did I kill her? It was really scary … And he said, ‘Thank you… You got her heart beating and if it wasn’t for you, we would’ve completely lost her.’”

“I do believe that everyone can be saved,” Bird added after telling her story. “I do believe that we need to try and reach out as much as we can… One of the things that we need to instil as professionals is to try and regain and re-establish hope in our communities and in our youth … offering as much programming as we can.”

Bird appealed to Sacred Circle for support in suicide prevention ministries going forward. “Work that we do is not fun, but it is something that we’re good at,” she said. “When we reach out, I hope to have as much support as we can get from this body, because this work isn’t easy. It’s one of the toughest jobs I’ve had in my life.”

Russell-Patterson outlined approaches that the church’s suicide prevention workers would take in the coming year. They planned to offer information sessions about suicide prevention and grief recovery by hosting free lunches, barbecues and community events. In preparation for pilot projects such as “From Trauma to New Life” in northern communities, they would partner with community members such as nurses, social workers, teachers, police, counsellors and clergy.

They also hoped to establish a support group for loved ones left behind after suicide or join an existing one, and to help individuals identify resources for suicide prevention and grief recovery using their own cultural practices, talking circles and activities.

“Collaboration is vital,” Russell-Patterson said. “Awareness, collaboration, communication, commitment and evaluation. That’s what is required to put a suicide prevention programme into place. Doing something one time [or] once a year doesn’t work.”

Pitching Our Tent

Pitching Our Tent organizers also hope to partner with community organizations to address the crises in Indigenous communities. The appeal aims to support the Northern Manitoba Area Mission, and larger goals of healing and self-determination, by providing more effective spiritual service delivery and wellness programs.

Bishop Isaiah Larry Beardy, who oversees the Northern Manitoba Area Mission and is also a co-director of Pitching Our Tent, opened the Sacred Circle session on the appeal. He introduced Meade, who placed Pitching Our Tent in the context of the broader crisis.

“Unless we work together, we are not going to be able to do and continue to do what we would like to see done for our people,” Meade said. He described Pitching Our Tent as “a vision that came over our elders meetings over the last number of years.”

“Pitching our tent—what does that really mean?” he asked. “It means that we’re going to have to … go back to some of our cultural ways of life. We’re going to have to live according to the spirit of the land, the spirit of the water and the spirit of the air that we breathe.”

“I don’t see any other way,” he added. “We have churches that are falling down in our communities. Some of our communities don’t even have churches and we’re depending on churches.”

An information package on Pitching Our Tent distributed at Sacred Circle stated that nearly all Indigenous people in northern Manitoba are members of a Christian church.

The main partner in Pitching Our Tent is Greatsky Sovereign Trust. Greatsky is named after Chief William Kitche-Keesik, also known as “Great-Sky.” Bishop Beardy, as vice-chairman of Greatsky Sovereign Trust, has written a letter to the Government of Manitoba alleging fraud in the signing over of 85 million acres of Indigenous land in 1908, with the signing of Treaty 5. The letter claimed title to 345,504 square kilometres of land, which it said were valued at $100,000 per acre ($247,000 per hectare); recovery of extracted resources, damage and immediate relief. Beardy also wrote a letter to Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby citing the same claims of fraud and requesting financial support from the Church of England.

McLeod, who co-signed the letter, said Pitching Our Tent hope these fraud claims might allow the appeal to repatriate wealth and bring it back into the community. He listed the main areas of investment by which the appeal hopes to address poverty, food insecurity and the housing crisis in Indigenous communities.

Food security is the first area of investment. McLeod said Pitching Our Tent had made an $85-million offer to purchase Eddystone Farm, a large agricultural operation in Manitoba’s Parkland region which includes 72,000 acres of land, 30,000 acres of timber, 2,500 head of cattle “and can basically grow all of the crops that we would need to feed ourselves.”

Housing is the second focus for investment. Pitching Our Tent hopes to take advantage of the federal government’s $4-billion Housing Accelerator Fund, which provides incentive funding for local governments to increase housing supply, by partnering with Boxabl, a company that sells pre-fabricated homes. Other areas of investment include energy and fuel and blockchain technology.

Author

-

Matthew Puddister

Matthew Puddister is a staff writer for the Anglican Journal. Most recently, Puddister worked as corporate communicator for the Anglican Church of Canada, a position he held since Dec. 1, 2014. He previously served as a city reporter for the Prince Albert Daily Herald. A former resident of Kingston, Ont., Puddister has a degree in English literature from Queen’s University and a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Western Ontario. He also supports General Synod's corporate communications.