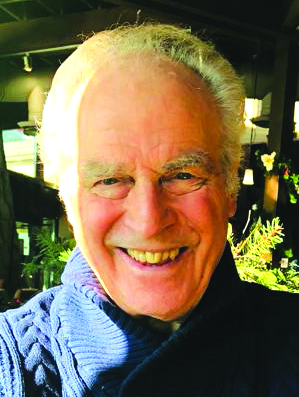

A nearly-lifelong atheist reflects on becoming an Anglican at 82

I recently debated the existence of God with an atheist/materialist colleague at Simon Fraser University.

I am an 82-year-old unable-to-retire post-secondary instructor with an interdisciplinary PhD in English literature and Kantian philosophy … and a recent convert to Anglicanism after a life spent mostly as a hard-headed, uncompromising atheist.

My debate opponent, some 20 years younger than me, was a recent apostate from Anglicanism … so the well-attended debate was aptly called “Crossing Paths.”

During the Q & A period after the formal debate, every question was aimed at me. One was, “How could an 82-year-old lifetime atheist and founder and chair for 40 years of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Society become a Christian?”

I was ready for the question; I had two answers.

First, I mentioned a brief exchange I’d had many years ago at the University of Toronto with the noted Canadian philosopher and Sachsenhausen concentration camp survivor Emil Fackenheim.

I was there primarily to talk over parts of my PhD thesis with my examiner, Northrop Frye. But I couldn’t resist talking to Fackenheim (decked out in a garish Hawaiian shirt in the middle of winter!) when I met him.

Knowing he was an Orthodox Jew considering aliyah—immigration—to Israel, I asked him how he had kept his faith while imprisoned in the camp and knowing what happened to European Jewry during the war.

His answer was short. I relayed it to the person who asked me the question at the debate:

“Graham, if we gave up our faith after the war, we would hand Hitler his ultimate victory.”

In my second answer to the question I spoke as a Christian: “Christianity, like no other religion, offers us the exemplar of a god who suffers with us. His tears watered the soil of Auschwitz.”

***

My own path to religion opened when I was very young. I am one of six children, and for some reason my Christian mom (certainly not my Jewish atheist father) picked me out of the six to take to Christian pre-school and then Sunday school in the nearby United Church of Canada church. And I went joyfully, loving every minute of it.

Then, around eight or nine years old, I joined a Christian summer camp in Surrey, B.C., where the family spent summers; it met outdoors Monday to Friday mornings and I stayed with it until I was 16, which is when I started working in the summers as a waiter.

Sometimes while waiting tables, I’d slip a gospel tract under the salt and pepper shakers. And one time—this was in the summer before I started at the University of British Columbia—a customer asked me about the tract. I told him I was a Christian and thought the good news should be spread as much as possible.

At this, he opened his valise and pulled out a book with the (to me) shocking and blasphemous title, “Why I Am Not a Christian” by one Bertrand Russell.

“You read the first essay in this, and I’ll read your gospel tract, and when I come back next week we’ll compare our reactions.”

The book dropped on me like a bomb … and almost immediately I shifted my first-year course load from pre-law to philosophy.

My first philosophy professor was an atheist, as were all, as far as I could tell, the professors at UBC; and they quickly convinced me that Russell was right: all religious thought was delusory, anathema to mental health and led down (or led from) the perilous path to political conservativism.

And there I rested, complacently, for 60 years.

Then, in 2017, came the first step in my conversion.

I had just offered a course at my university called “Imagine There’s No Heaven: A History of Atheism.” The course filled immediately upon its announcement, and when it was finished, I asked the dean what she thought of offering a sister course, “Imagine There IS a Heaven: A History of Theism.” She agreed … and the course double-enrolled!

Of course, I had no credentials to teach such a course … all the theology I knew was from my beloved John Milton—and of course my Sunday school and summer-camp teachers.

So I read everything I could get my hands on—Barth and Bultmann, Bonhoeffer, Niebuhr, Fleming Rutledge, Rosemary Ruether, Elizabeth A. Johnson, Dorothee Sölle, Karen Armstrong … and it was revealed to me, in spite of everything I had been taught and that was echoed in our secular society: One can be hugely intelligent and religious!

The theism course ended on what appeared in the course calendar to be a sour note: “Last Lecture: Christianity after the Holocaust.”

I had a German student in that class, about my age. I had learned German to read Kant in the original, so I always enjoyed speaking German to her. She had lived in Germany during the war, and I knew she would be apprehensive about the last lecture, thinking I was going to give a blanket denigration of German society.

The exact opposite was my intention, which was to talk about the great German religious figures who kept and fought for their faith against the Nazis: Edith Stein, Bonhoeffer, Martin Niemöller, and the courageous young White Rose dissidents, all of whom held to morality in the middle of hell.

After the class was over, a line of students formed to thank me. The German woman was at the end of the line. When she approached me, she silently reached around her neck, took off her rosary, and put it over my head, and wordlessly walked away.

Was that moment epiphanic?

Over the past six years I’ve often thought so. In late 2022, after spending some time worshipping with the Canadian Reformed Churches, followed by some months of church-shopping spurred by doctrinal differences, I paid a visit to a small Anglican church in nearby Burnaby, where I met the minister and her wife. This was late in 2022. And for many months now, I know I have found my spiritual home. I love the combination of inclusiveness and ritual and traditional hymns; also, of course, I didn’t have to “cross my fingers” any more when the issue of free will arose (anathema to the Reformed church, which is rooted in the teachings of Calvin).

I joined the choir immediately, and now perform the gospel reading from the pulpit.

Thus my eager and earnest willingness to defend my love for God and the Anglican church in the debate I referred to earlier.

The debate went well. It began with my antagonist contending that “religion is the garbage dump of scientific materialism.”

When my turn came, I agreed with him. I said in rebuttal that I’m fine with religion being relegated to the dumpster; that’s where it belongs, if and insofar as it is a medium for male chauvinism, for discrimination against gender minorities, for scriptural literalism, for hideous teachings of hell, or pandering to human wish-fulfilment through pie-in-the-sky teachings of heaven, or interfering with women’s rights or the rights of those who wish to die on their own terms—and a panderer to political interests. So an ironic thank you Freud, and Marx, Nietzsche and Bertrand Russell and the “new atheists” for reminding us that religion should not be made the handmaiden of power structures. The god these atheists dismissed is not the loving power that guided Ruth and Esther and the poet of the psalms and the wisdom of Ecclesiastes and the beautiful scrolls of Isaiah which inspired Handel’s Messiah. It is not the loving power who brought us the gifts of free will, the grounds for absolute morality and conscience, the love for music, or language, or love, or the disinterested affection for natural beauty.

The great writer and humanist Elie Wiesel told me a story once when I met him in Vancouver many years ago, shortly after he won the Nobel Peace Prize. He was 15 when he was shipped to Auschwitz. This is what he saw one night in Auschwitz: some Orthodox rabbis gathered together and decided to put God on trial in absentia for criminal negligence. They elected a prosecutor, a defence lawyer, a judge and a jury of mixed onlookers.

God was declared guilty as charged.

Whereupon the chief rabbi, seeing there was present a 10-person minimum minyan (quorum for Jewish worship), said,

“Now, let us pray.”

Lex orandi, lex credendi!